Ukraine as a Character

Why is disinfolklore an appropriate moniker? In disinfolklore, we look at characters in the stories we’re served up. Ukraine is a damsel in distress who must be rescued by Donald—this is how he’s trying to archetype Ukraine. We know it’s obviously false. Ukraine is a damsel in distress who must be rescued by Russia because of the coup and all of these trolls. Or Ukraine is a damsel in distress who must submit.

We go back to coercive control. We go back to the people many of us might have met in our lives who come from the perspective of realpolitik. They say, oh yes, isn’t it awful what Russia is doing? But honestly, it’s time to just—you know, Ukraine just needs to give up Donbas and everything will be fine, and we’ll be able to get back to our cappuccinos and whatever.

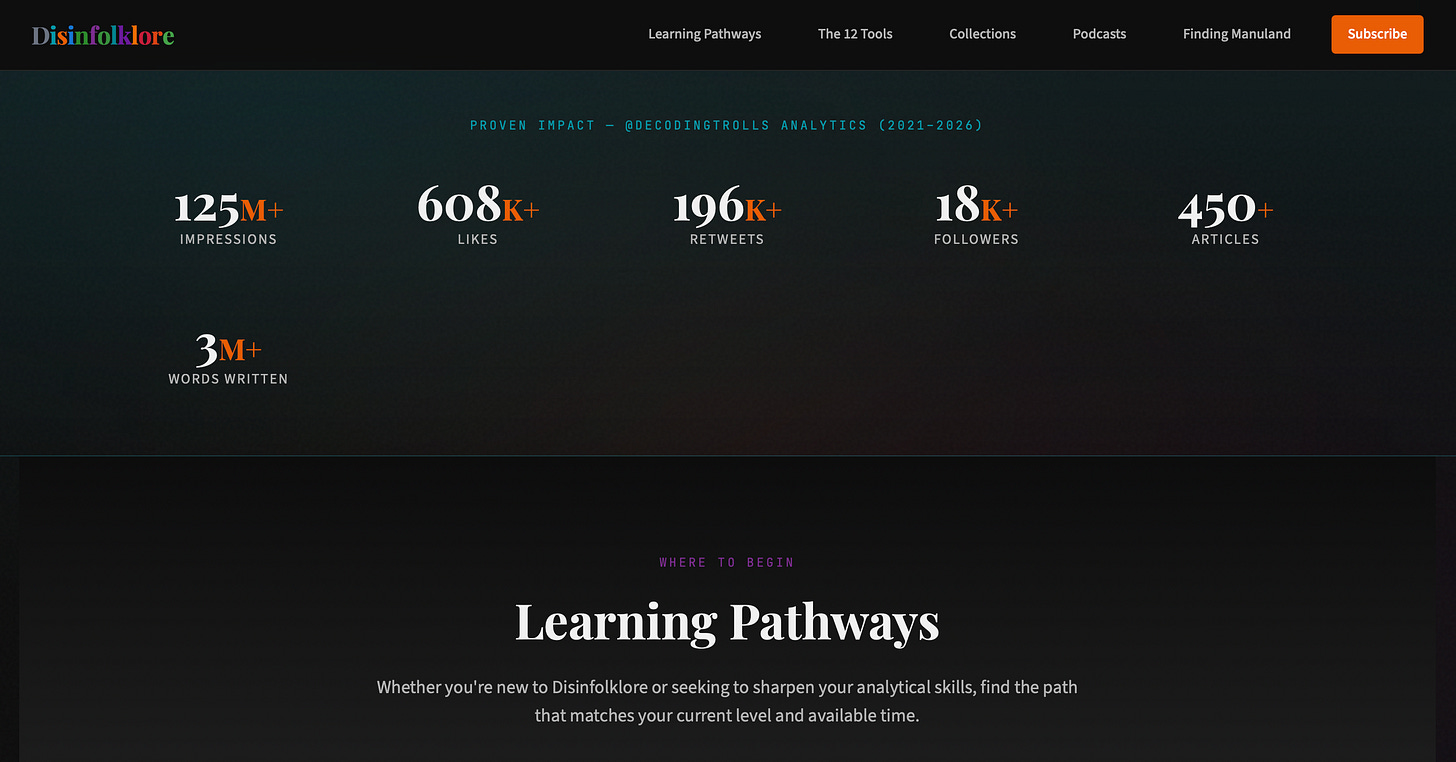

I’m going through a thorough reorganisation of my work and approach to teaching. Watch this space. Here’s a sneak preview of part of my new homepage, and of what is coming:

What’s going on there is Ukraine is being archetyped as a character. Ukraine is a country of 42 million people, a very complex concept. It’s a geographical space. It’s a historical context. If we take the disinfolklore lens, then it’s quite natural for us to see anything in a meme as a character.

Abstract Concepts as Characters

Obviously when we’re looking at Netflix or a story in the news or any art or play, we have characters manifesting as individual humans. What the disinfolklore analytical method allows us to do is perceive how abstract concepts take on the characteristics of characters, of personalities.

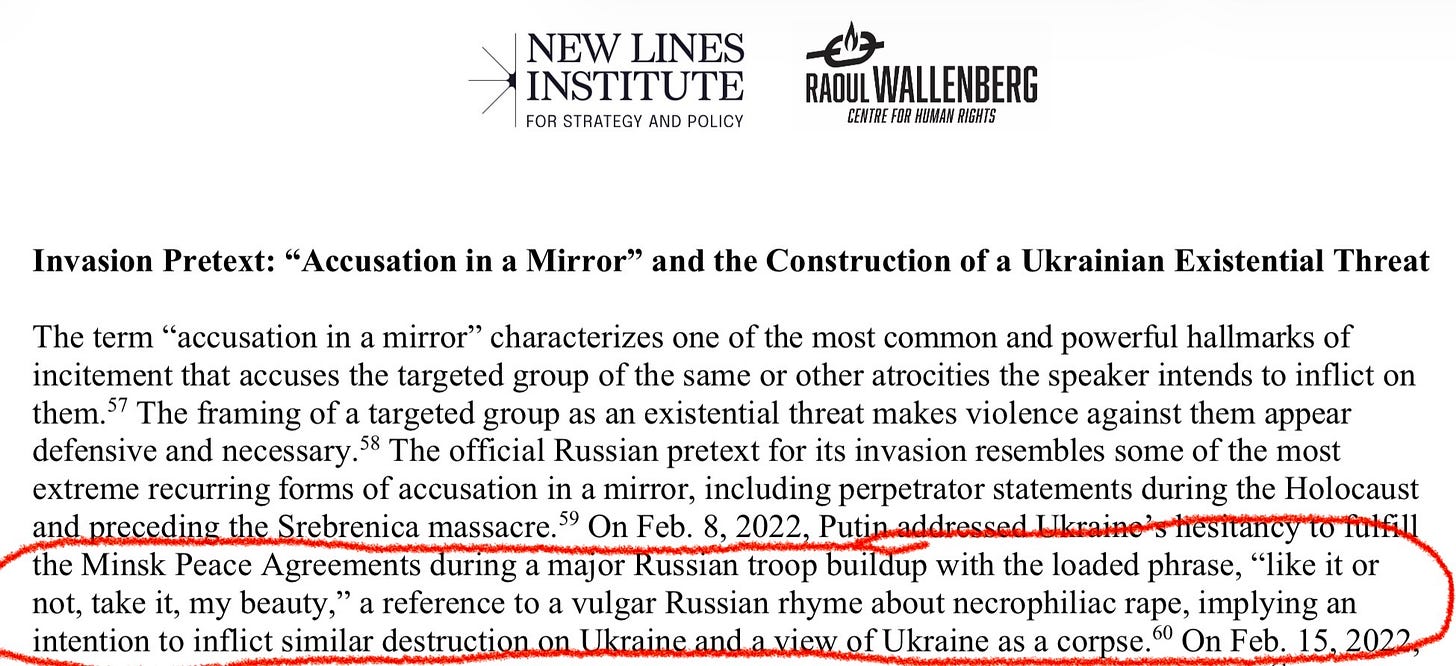

This is one of the main means by which Russia’s disinfolklore manipulates us—because we don’t notice it. We’re not looking for it. We’re not looking for the energy of character in an abstract concept like Ukraine. Putler then can talk about Ukraine as a corpse, as a dead corpse, as a dead woman who is worthy of becoming a victim, as in that song by Red Mould which I’ve talked about before—*Sleeping Beauty in the Coffin*. International lawyers use it as evidence of Putler’s intention to genocide Ukraine, because he quoted this disgusting lyric which I’m not going to repeat here—*Sleeping Beauty in a Coffin, I Walked Up and XXXX her…*

This archetyping through characters is a phenomenon that very few other so-called disinformation researchers, or people watching propaganda, or people interpreting data have noticed. I’ve not only noticed it—I’ve tried to think about it, work it out, and articulate what is going on.

It’s quite natural, if you look at disinfolklore as a narrative form, to see how Ukraine is being archetyped as a particular character with characteristics.

Don’t Poke the Bear

Russia does it when it calls itself a bear and promotes this troll. I first came across this with an American senior officer, a colonel, who once in eastern Ukraine just mentioned to me about the bear—“don’t poke the bear.” That was the first time I came across this meme.

What this actually is, is archetyping Russia as the strong bear, which you can’t do anything about when it pokes you—you can’t poke it back. If it pokes you, then it’s your fault for poking it. It’s a really complicated, psychologically manipulative set of mental routines it sets off in our minds. That is concealed by the use of a bear, which we think of—well, those of us who didn’t grow up in Central and Eastern Europe with bears running around, or in Pennsylvania where bears are actually running around. Those who grew up in bourgeois Western Europe haven’t come across bears except in fairy tales and folk tales.

That for me was a clue of how Russia uses character in stories. Donald uses the same trick, and many propagandists use the same trick. It’s also a means of critiquing what they do. Russia is the implacable bear—better get over it, Ukraine.

Stereotypes versus Archetypes

Stereotypes are delivered through the storytelling and newsy memes every time Druidy Don, Donald, Duncy Putin, or their henchmen and women speak in disinfolklore.

When I speak of archetypes, it’s much deeper than mere stereotypes. I’m not just saying we’re reifying reality, aggregating components into a trope. Archetypes connect deep Indo-European cognitive structures with particular aggregated ideas—like the data-resistant archetype of a Potemkin state.

Data-Resistant Archetypes

I was reminded this week, reading a politician’s speech from a formerly occupied part of the former Soviet Union, where they were talking about NATO as if the past three years hadn’t happened, or as if America’s threats to invade NATO hadn’t happened. They were talking about how the Collective Security Treaty Organisation, which is Russia’s fake NATO, has Russia as a necessary component in it. Have you not seen anything in the past three years? Have you not picked up the data? Have you not updated your archetype of the CSTO, of Russia, of NATO, of the past few years?

These characters have changed. They’ve been transformed. You’re talking about NATO and Russia from Act One of the play. Those of us who have been watching avidly for the past four years, day by day—these characters evolve and develop. We are now in Act Six, and the character of NATO is not what it used to be.

Some of us will have seen reference today to how a drone, suspected to be a Russian drone, penetrated Polish airspace and crashed quite far into Poland, right near—or maybe it didn’t even crash, maybe ran out of juice—near a Polish base which is rumoured to be one of its main electronic warfare facilities. Nobody there knew how to shoot it down. They couldn’t shoot it down.

This idea of NATO as a bear has to develop, just as the idea of Russia as the bear has to develop. When I talk about data-resistant archetypes of a Potemkin state, I’m using literary references with the idea of a character to articulate how these signifiers like Russia or NATO—their actual contents can transform.

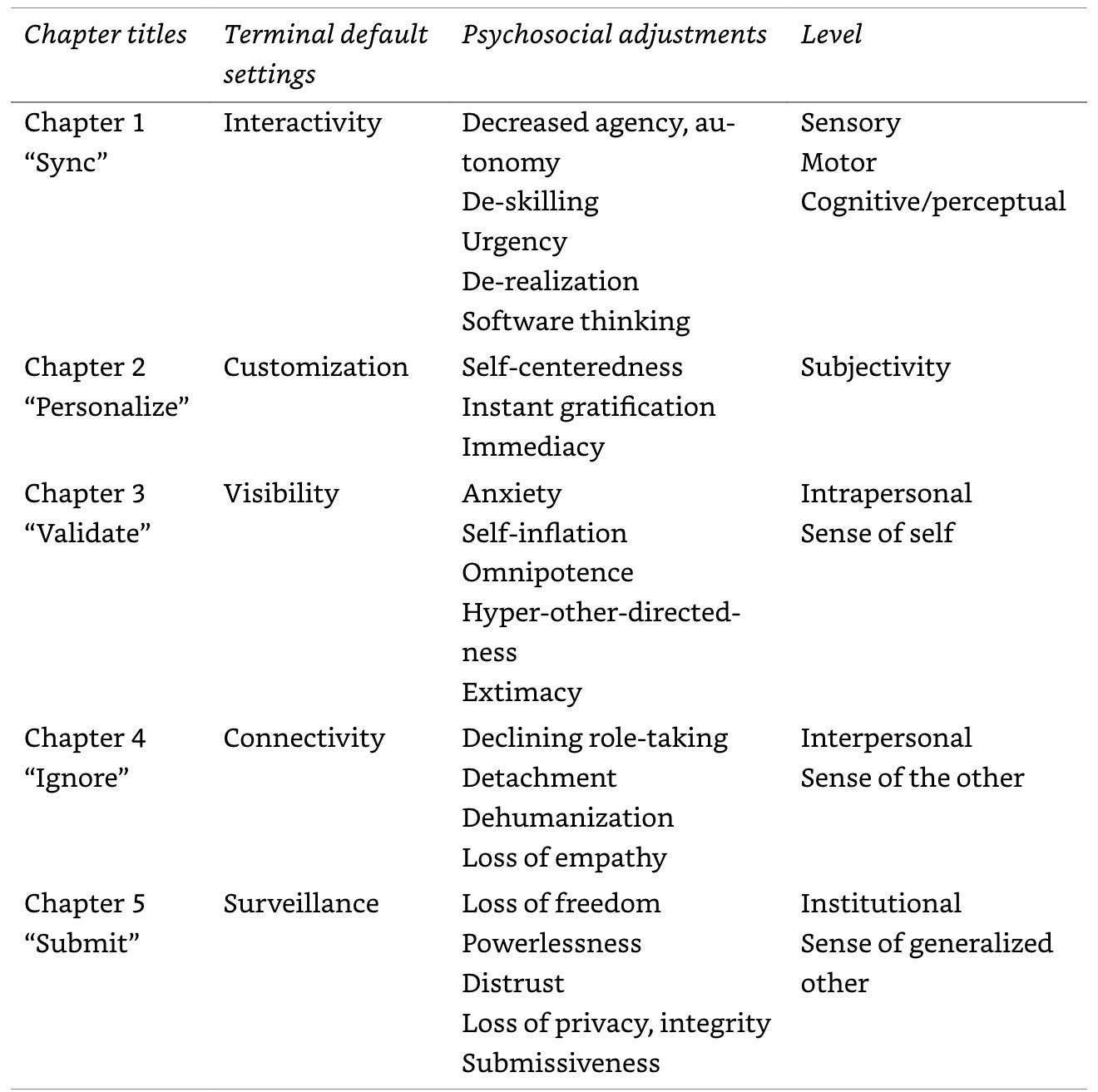

Too Much, Never Enough

When I speak of disinfolklore’s archetyping, I’m talking about a process that takes many different words and meanings, imbues them with dynamic characteristics, then does it again and again and again—too much and never enough. That phrase is basically the title of the biography of Donald by his niece, but it’s also what characterises hyper-modernity as distinct from post-modernity, modernity, or the classical period. Too much, never enough—acceleration and insufficiency.

Before we know it, we’re inside a MAGA universe wrought by disinfolklore. It’s the system effects of all of these aggregating characters in the stories that we are embedded in, which are broadcast through the news, repeated by Donald and by many others all the time—including ourselves. The aggregating effect is that we’re put inside this MAGA universe.

Inside the Usurpers’ Universe

I’m using a metaphor here—the idea of being put inside a universe, a MAGA universe, but also inside a Russian universe. This goes back to what I talked about at the beginning and what James was talking about at the beginning. The whole point of the Kennedy Center is just one of tens of thousands of vectors for each of us which could have the impact of transforming our identities and our surroundings and turning the usurper’s reality into an irreversible reality.

As it goes, I think the disgustingness of what we’re gradually learning about the whole Epstein stuff—the enormity of it, Donald’s complicity in it, Putler’s complicity—it would be somewhat ironic if Epstein brings them down. Out of all Putler’s crimes, this is the one that ends him.

International Relations as Storytelling

The stock in trade of international relations professionals is storytelling, as if the phenomena they speak of are more real than characters in a folktale. The West, NATO, Russia, strongmen, spheres of influence. As many of us see and understand now—this great German word for Putin understanders—they impute intention to this character called Putler who doesn’t correlate in any way with the biological human called Putler. It’s layers and layers away from the biological human biped, yet they write very earnest essays in *Foreign Affairs* and their escalation management logic dominated and colonised the minds of the people in former President Biden’s administration, as all of us understand so well.

This whole discourse in international relations—IR itself—is a form of storytelling. If you’re coming from a disinfolklore analytical method point of view, you can look at it just like storytelling. You look for the characters they’re talking about—don’t poke the bear—and all of this chatter about Westphalia and all that fascist civilisations stuff. These are all just storytelling, which has the same value, effect, potential for manipulation, and status, in my humble opinion, as any piece of news or anything coming out of Donald’s mouth.

I reference Donald a lot because he’s a fairy tale character we’re all very familiar with—he’s sadly part of our everyday reality. I could just as easily be referencing someone else if this were a different age or a different moment.

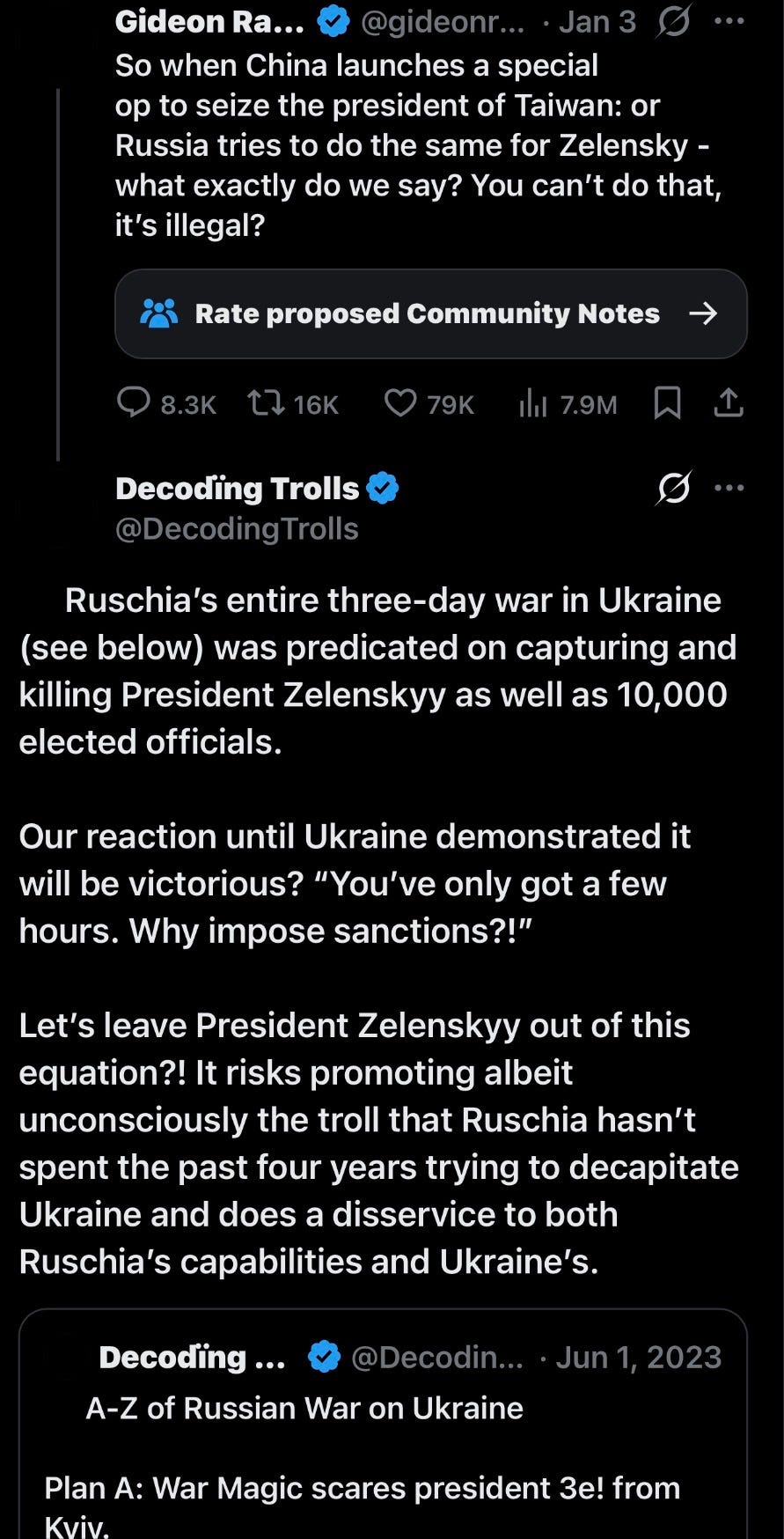

The Gideon Rachmans’ Problem

Quite serious people impute into the character I call Duncy Putin, or Russia, the characteristics of a bear—they do it unconsciously. They’re earned archetypes or reputations. Ukraine as a lion—that’s a weak encounter archetype in that sense.

This guy Gideon Rachman—I’ve mentioned him before, just because he’s a good example of how this old guard don’t have a disinfolklore perspective. They can’t see how they impute these ridiculous thought routines to Putler. For instance, as we’ve seen when the United States began to occupy Venezuela, even though it doesn’t seem to be admitting this or understanding it, and started to trigger a whole set of legal obligations which it is pretending to ignore by kidnapping the fake president of Venezuela—Gideon Rachman said Putler is going to look at this and decide to do the same to President Zelensky.

What are you talking about? What level of lack of sophistication are you living on that you think Putin thinks this way? That you think it’s legitimate for the foreign editor or whatever he is of the *FT* to reveal how ignorant you are—how you cannot see that you’re actually talking about a cartoon character in your mind who’s occupying space in your mind? This Putin who’s walking along merrily, going: “Oh, I’m doing this full-scale war against Ukraine for eight, nine years, and I’ve just spent 1.3 million men. I tried to invade Kyiv. I lost the Battle of Mostyshche. We had to withdraw.” “Oh, but now Donald has invaded Venezuela. Now I feel permission to do the same to President Zelensky. God, thank you, Donald, for doing that, because now there’s this precedent.” On so many different layers, it’s really dumb.

If you’ve got a disinfolklore perspective—and all of us are not picking on him, well, I am obviously, but I don’t mean to, because there’s many things that I probably fall for the same type of trolls. With a disinfolklore perspective, I try to critique what I say in the same way—just looking and recognising: I’m not talking about Putler here. I’m talking about a character. He’s an invented character. It’s like in a Netflix series, but I’m imputing real characteristics to him that don’t correspond to reality. I’m trying to communicate something through telling this story that Putler will see Donald has invaded Venezuela and then decide to act. It’s total fiction because, as we all know, in reality Putler has tried to do this like 4,000 times already.

Re-Archetyping Ukraine

There are these data-resistant archetypes which underpin characters like Ukraine. Other archetypes are emerging or fading or enduring. All of us are watching in real time the re-archetyping of Ukraine in the minds of, for instance, European leaders who realise European security now depends on Ukraine.

Donald hasn’t got the memo, or he just doesn’t care—he just wants to destroy Europe. He thinks Putin is a good means of doing that. If Ukraine would just submit, then Putin could invade Moldova or Poland, and that will totally collapse the euro, and that will make America great again. Maybe that’s what Donald thinks.

He certainly doesn’t see Ukraine as a protagonist, or as a main protagonist. That gives Ukraine an edge, because it’s got in President Zelensky and some of the people around him—people who do think through what they’re dealing with, not using the terms of disinfolklore, but thinking about it the way we think about art or script writing. President Zelensky has this intuitive sense of understanding character and archetypes and storytelling, and how characters can change and must change and do change. Therefore, if you can harness that, whether it’s in propaganda or disinfolklore or your own nightly speech, you yourself can in real time transform the character of Ukraine—re-archetype it into what it substantively is and has been for the past 6,000 years: the key, the origin, and the source of innovation in Indo-European culture.

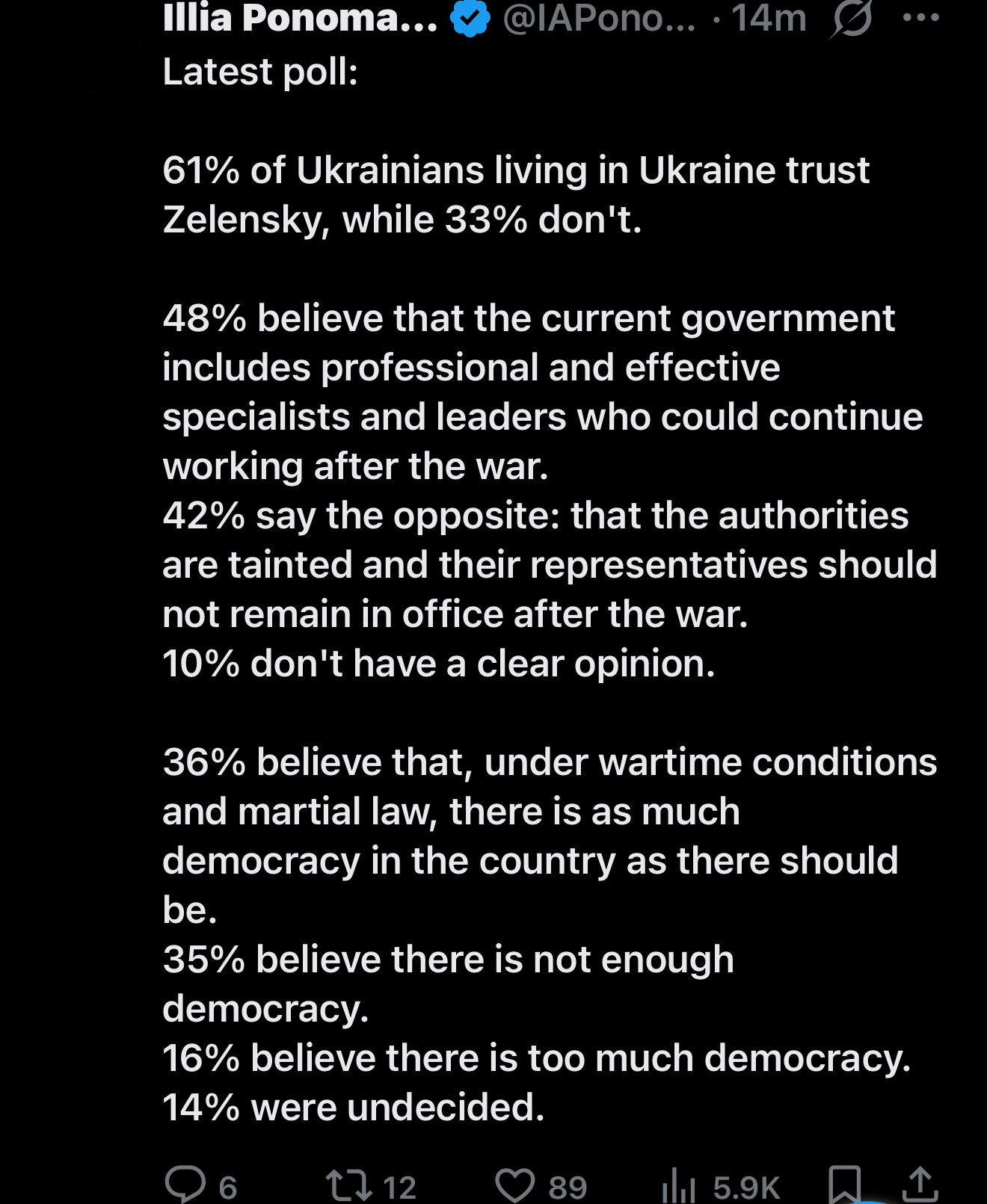

Zelensky’s Enduring Popularity

I note, en passant—if you’ll pardon my French—that polling today reported President Zelensky is at 61 or 62 percent in Ukraine. He won the election on 64% in 2019. Now, seven years later and all that has happened—zillions of memes, zillions of disinfolklore from Donald, from Putler, helped by missiles, the complicity between the missiles and the stories about the missiles, the fear and the future and Ukraine capitulation—despite all of that, President Zelensky’s level of popularity persists and subsists.

That demonstrates how we can defeat disinfolklore. The stories, and the stories about the events like missile strikes, about corruption, about all of the nonsense—Ukraine gives this great example. We can think about it as the character who’s on a journey, the hero’s journey or the heroine’s journey. She begins life on 64, and now she’s still on 61 after all of these travails and adventures. Well, that probably wouldn’t make a real hit—you really want her to go up in popularity or build down in popularity.

I make this observation from the point of view of thinking that these disinfolklorists will necessarily win, that disinfolklore necessarily manipulates. Obviously we do see it has great effects in some places at some times, and it has had in the past in Ukraine. At the moment, it’s a good example of how we can overcome it.

I’ll leave it there for tonight.

Continued from:

First in series: